Minor Miners – Child Labour in the Coalmines of India.

My personal project “Minor Miners” seeks to highlight the human cost of resource exploitation by exploring the working situations and root causes of rampant child labour happening in the highly unregulated coal mining industry of India. It studies the working and living environments of these children and their families, examining their backgrounds and how it has affected their decisions in life. It will also drill below the surface to reveal the reasons that compel these parents to make these impossible decisions to send their children out to work in extremely hazardous conditions for long hours instead of to school.

Even as India is seeing an average economic growth of 8.4%, crushing poverty and malnutrition are harsh realities for millions of children. India has the largest number of child labourers under the age of 14 in the world with an estimated 12.6 million children engaged in hazardous occupations like mining. In the poor’s struggle to feed their young with no help extended to them, they are forced into hopeless situations. “Minor Miners” is an ongoing self-funded project on child labour and their trampled rights, and the root causes such as loss of livelihood, poverty and gender discrimination besides other socio-economic issues that isolate these families, cornering them into taking desperate measures.

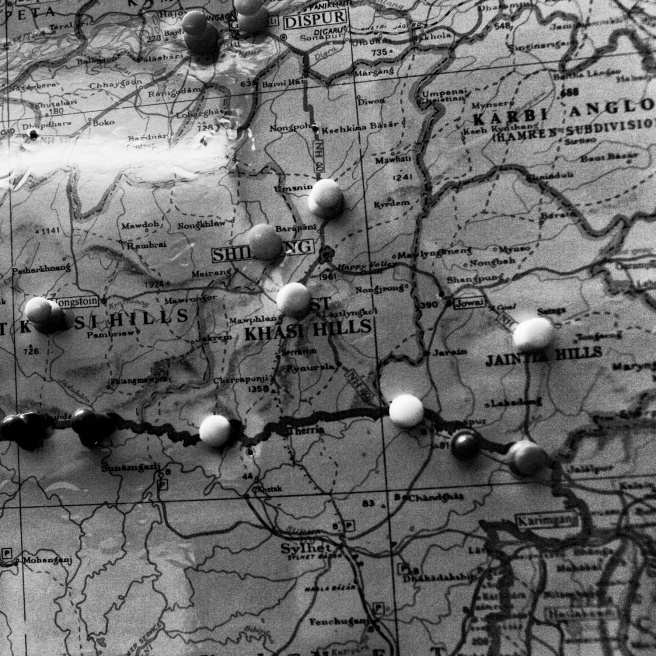

Thus far, this story has been photographed in two states along India's coal ‘belt’, focusing on young children who are sent out to work in hazardous conditions at tender ages, earning less than a dollar a day. I have visited mining towns along the ‘coal belt’ of India’s uncontrolled mining industry, regularly seeing children as young as 6 working in the mines. They work long hours from dawn to dusk either crawling in wet coal 250 feet underground in unstable and unscientific mines where dynamite rods are carelessly used to extract coal, or carrying inconceivable weights of coal on their heads, walking for long distances over scorching and hazardous coalfields which threaten to buckle as the underground coal fires rage out of control. In Jaintia Hills, they work in unmonitored and extremely dangerous underground coalmines dug out by children, who are preferred by mine owners for their small bodies and cheap labour costs, using primitive methods and tools. This north eastern Indian state of Meghalaya sits on about 640 million tons of coal, with 40 million tons of that in Jaintia Hills alone which has about 5000 privately owned mines, many hiring children.

Besides being deprived of the basic human needs such as clean air (sulphurous methane gasses escape from large cracks in the ground as coal fires rage beneath the earth in the coalfields), clean water (in many cases, rain water pumped out of the flooded mines are reused for daily needs, causing water toxicity poisoning), basic sanitation, and a stolen childhood, these children also have no access to education or healthcare. In fact, these daily-wage workers are completely uninformed of the adverse health consequences of working in a mine such as chronic lung diseases such as pneumoconiosis (black lung), hazardous gasses and water toxicity poisoning, and carcinogenic risks leading to reduced life expectancy, besides traumatic injuries caused by roof collapses and rock falls. In Meghalaya, deaths by entombment and tunnel flooding often go unreported. Another child may be sent in to remove and dispose of the body. Sometimes the mine owner pays a small sum of about $250 to the family, but mostly, if the children are lone migrants, families and authorities are not even notified.

Having witnessed the working and living conditions of the children, I hope to continue the project by traveling to their origins, asking the questions that I feel are largely ignored when it comes to the issues of child labour i.e. what are the social (eg. caste discrimination) and economic desperations they are confronting and the obstacles that are preventing them from being able to pull themselves out of the crises. Visiting their origins will also allow the project to examine how it can be eradicated. How displacement or loss of livelihood in the places they come from can lead the illiterate, unskilled communities to poverty and starvation, which then drives them into slums or migration and to such desperate measures as selling their children. The work will culminate with a series of photographs and multimedia pieces including audio and video, which I hope will then evoke changes that will help this neglected social class pull themselves out of the vicious cycle of life.

I intend on working hand-in-hand with a grassroots NGO, Impulse, based in Shillong, Meghalaya, that has been working on the issues of child labour and trafficking in the north-eastern region of India for a decade. Together, we will travel to the source points of the trafficked children in Nepal and Bangladesh to continue this investigative project.