Even though “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” implemented during the Clinton administration in 1993, has recently been repealed, there have been considerable effects from the ban on homosexuality in the military over the years, the aftermath of inequality, discrimination, harassment and mistreatment based on sexual preference. The issues follow a long history of human and civil rights abuses that LGBT service members have experienced resulting in lost careers and damaged lives. Prior to the enactment of this policy, all recruits were asked about their sexual orientation before being permitted to serve, and service members suspected of being gay, lesbian or bisexual were questioned and threatened with court martial or prison if they did not divulge the names of other gay service members. In many cases, these men and women - highly skilled, well educated, patriotic and courageous - attained high rank, received numerous medals and held top-level jobs that were essential. And yet, as one former IT Navy Specialist stated, was prejudice was still rampant in the armed forces and policies existed “to get rid of the dead wood in the military: drug addicts, sex offenders, domestic violence perpetrators and especially homosexuals.”

The ban against homosexuality compromised the safety - and DADT failed to protect the legal rights - of a significant portion of the military. From the first soldier discharged in 1778, to Petty Officer Allen R. Schindler, Jr. who was brutally murdered by a shipmate in Nagasaki, Japan in 1992 to Major Alan G. Rogers, the first known casualty in Iraq who was gay and whose sexuality was not disclosed by the Pentagon, LGBT service members have suffered extreme costs to their careers and lives. The policies prohibited service members from receiving honorable discharges and lost benefits accorded them for serving their country, sometimes under extreme conditions of combat zones. In many cases there was no recourse. Service members continue to suffer the effects, seek justice or apply for reinstatement. Many suffer the same medical, physical and psychological effects of war. Devotion to their country goes unnoticed.

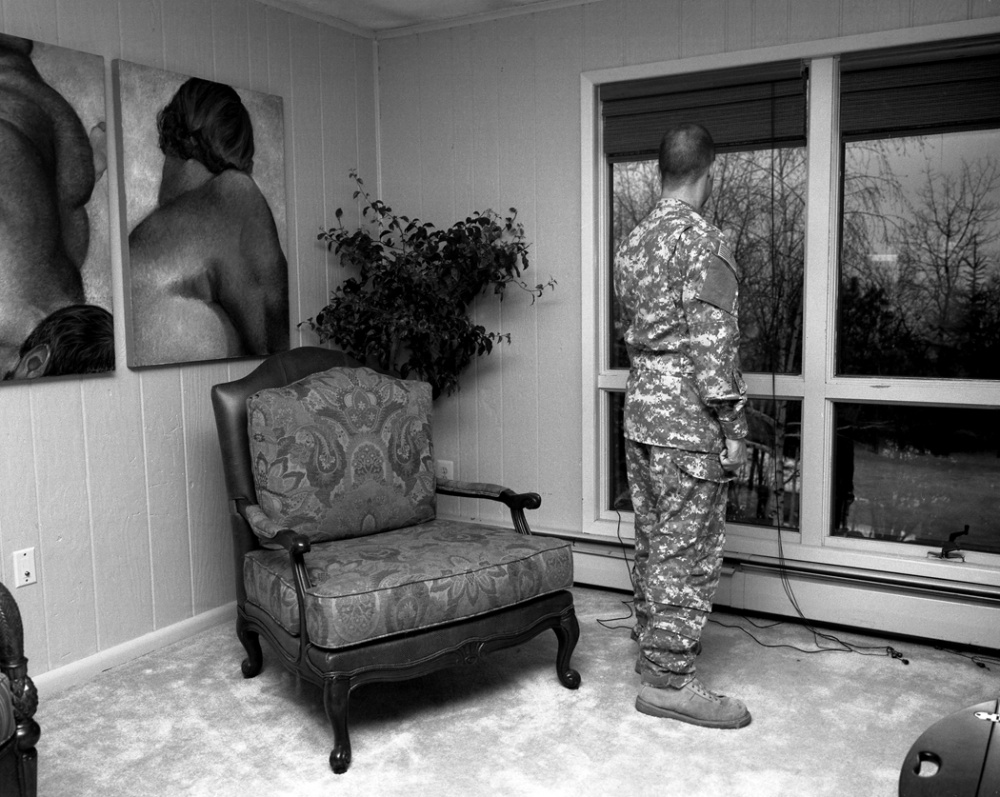

The aftermath of this history is devastating. I have interviewed and photographed over 100 subjects, in the privacy of their homes, from different geographic, socio-economic, ethnic, religious and racial backgrounds, and from all ranks in the military, ranging from a 92-year-old World War II veteran (and his partner of 65 years) to recent enlistees and active duty personnel.

The visual and oral histories reveal marked differences throughout the decades in the effects of discrimination and homophobia in the military based on cultural, social and political milieu, religious background and geographic location. The narratives recount incidents of unjust protocols (prolonged interrogations leading to cognitive and psychological damage); hazing (forced to simulate oral sex on fellow soldiers during ‘training’ sessions or covered with dog feces, caged and left in kennels); sexual harassment, violent rape (male-on-male) and abuse; mandatory outings of fellow service members; profiling, blackmail, betrayal and verbal abuse resulting in the forced dismissal of tens of thousands LGBT service members (over 14,500 during DADT alone). Stories of survival exist. LTC Victor Fehrenbach, 20-year F15 fighter pilot; 88 combat missions; 400 combat hours, successfully fought his discharge. LTC (jg) Don Bramer, intelligence officer with top-secret security clearance and multiple deployments to the Middle East, continues to serve despite suffering from PTSD. The stories continue.

While working in my studio one day in November 2009, I heard a radio interview of Pvt. Nathanael Bodon’s mother recounting her son’s discharge while serving in Iraq - an outing by a fellow soldier in his platoon who had seen photographs of Nathanael kissing his boyfriend on his blog. She said she feared for her son’s safety since he was harassed repeatedly. Her voice trembled; she was proud of her son. I sat silently and felt angry that injustices toward LGBT military continued after years of struggle. I began to search the internet for her phone number to ask if she would put me in touch with her son. I needed to do something; but I didn’t know what it was at the time. I didn’t know I would spend the next two and one-half years becoming involved in the lives of people who were not much different than me – being gay - but whose worlds and experience were vastly different than mine. However, I remembered the secrecy I lived with while growing up, the occasional denial of my sexuality and the attacks I sustained as a young man. I was angry, but more importantly, I was compelled to explore how many lives had been affected by homophobia.

In the 1970s I had been involved in anti-war movements and in the 1990s, I volunteered with NYC’s Anti-Violence Project. My understanding of their choices was blurred. I had to come to terms with my feelings about the military and why LGBT service members would be part of an institution that was antithetical to non-violence. I researched DADT and read books on the history of the ban on homosexuality in the military. The fight to repeal DADT was in full force after President Obama’s election in 2008. I began attending lobby days on Capitol Hill with national organizations involved in the repeal of DADT. I contacted service members and veterans through social networking sites and LGBT military alumni associations and compiled a list of over 200 people whom I could interview and photograph. Pvt. Bodon’s case was not uncommon; thousands of stories have gone untold. The more I read, the more I understood how simply a person’s life and career could be destroyed and that the underlying issue was a breach of civil and human rights and that every person has a right to choose how to serve their country based on their beliefs.

Beginning May 2010, I traveled the coasts of the United States with grants from The New School University and The Palm Center. Over a ten-week period I recorded oral histories and made environmental portraits of 50 veterans and service members. The interviews were conducted with analog audio and photographs were exposed on medium format black-and-white film. In the subsequent two years, I made numerous trips to other regions and continue to interview and photograph more veterans and active duty service members who can now speak openly about their experiences post-DADT. Traveling to their homes provided (and continues to provide) a sense of intimacy and safety while evoking the private nature of sexual orientation.

Ultimately this material will be archived in the Rare Books, Manuscripts and Special Collections Library at Duke University as a research collection. SLDN and OutServe, organizations that continue serving the LGBT military community, utilize the photographs. My hope is that through public exhibitions and forums – reading/hearing stories of victims of discrimination in their voice and humanizing issues through portraits – this work will empower the LGBT community and educate others to the struggle of a community that continues to be marginalized.