View of the Atlantic Ocean from S. Miguel island, Azores, Portugal, on 22nd January 2021. The sea was always what connected and separated Azoreans from the rest world, especially in North America, which they saw as a place where they could find a better and more prosperous life.

To repatriated Azoreans, this body of water is like a prison wall that separates them from the life and family that they left behind, making them call S. Miguel island their Alcatraz. Since 1996, when the immigration law changed more than 1,464 people were repatriated to the Azores.

José Pacheco looks through a window in the shelter home that he has been living in for the last 11 years in Lagoa, Azores, Portugal, on 28th March 2021. José emigrated with his parents to North America as a toddler. After a car accident that left him hospitalised, he got hooked on opioids which took him to drug addiction. He was deported after completing a sentence for drug possession and dealing.

Once they land in the Azores, repatriates receive aid from local NGOs, that provide them shelter, food and assistance to get legal papers. Many repatriated due to lack of working opportunities, psychological issues and/or addictions become completely institutionalised.

Amílcar Raposo closes his jacket before heading to a food bank to pick up his monthly groceries in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 27th October 2020. Amilcar moved to the US when he was five years old and worked most of his life in the textile industry in Fall River, Massachusetts. Before the change of immigration law in 1996, he served 7 years of a 10-year drug-related sentence. In 2006, after being accused of domestic violence was taken into custody and sent back to the Azores.

Amílcar can’t find a job due to his age but also to a lack of work opportunities. Like many repatriated he is dependent on state welfare and food banks. Some repatriated because of their past engagement in small traffic, and other illegal ventures to make extra income.

Evelina Bernardo (in white) hangs out with others repatriated in an alley where they spend days drinking in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 31st May 2021. Evelina has a past covered with abuse, violence and addictions. After serving a 9-month sentence on drug-related charges, she was deported to the Azores, where she worked on the streets becoming HIV positive. Evelina lives in a shelter home but spends the days in the alley getting drunk and wishing her death.

A history of violence and addictions is common to many repatriated, but to many others, the realization of loss, abandonment, lack of opportunities, economic hardship, and social stigmatization leads to depression, substance abuse and ephemeral life.

Chico hugs Evelina as a way to show his friendship in the alley where they spend their days drinking in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 28th May 2021. Due to her health problem, Evelina relies on other repatriates to take care of her while they hang out in the alley. They get her wine, and cigarettes and help Evelina get back to the shelter home once she is too drunk. In return, she shares some of her wine and cigarettes.

The majority of repatriates don’t have any family on the island, and the ones that have usually are not welcomed due to the stigmatization that Azorean society reserves for them. Instead, they create social bonds and family ties with people that live with and face the same problems.

Jorge Machado goes on his morning walk routine around the streets of Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 23rd November 2021. Jorge volunteered to be a US marine in 1972 but was never sent to Vietnam due to the only-son policy. He was charged with a violent crime when his house was robbed. After serving his sentence, Jorge legally tried to avoid deportation but due to a petty crime committed at a young age, got deported through the retroactive effect of law.

The retroactivity of 1996 law implements someone can be deportable for crimes committed at any point before the change in law, including crimes that were not deportable offences at the time they were perpetrated.

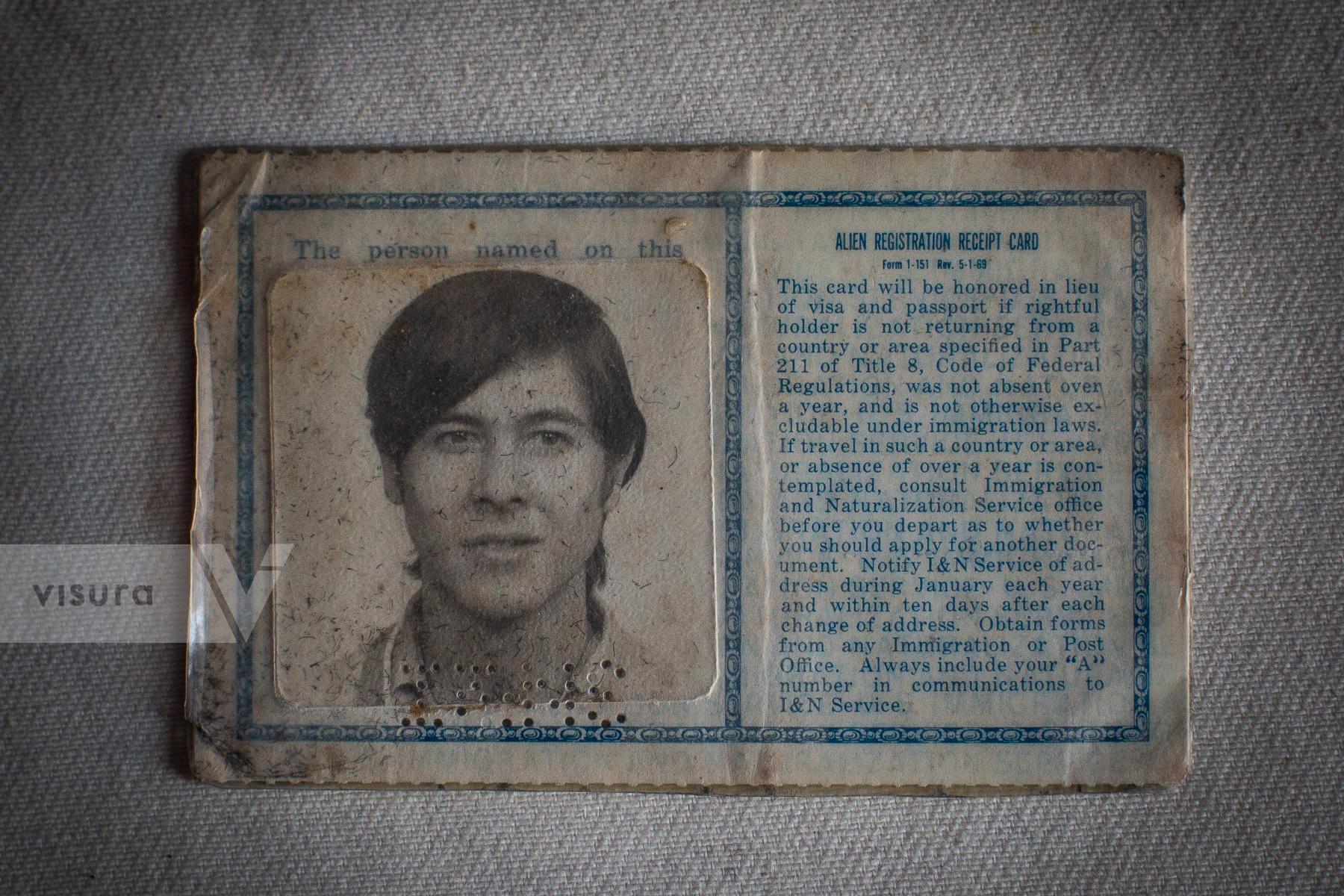

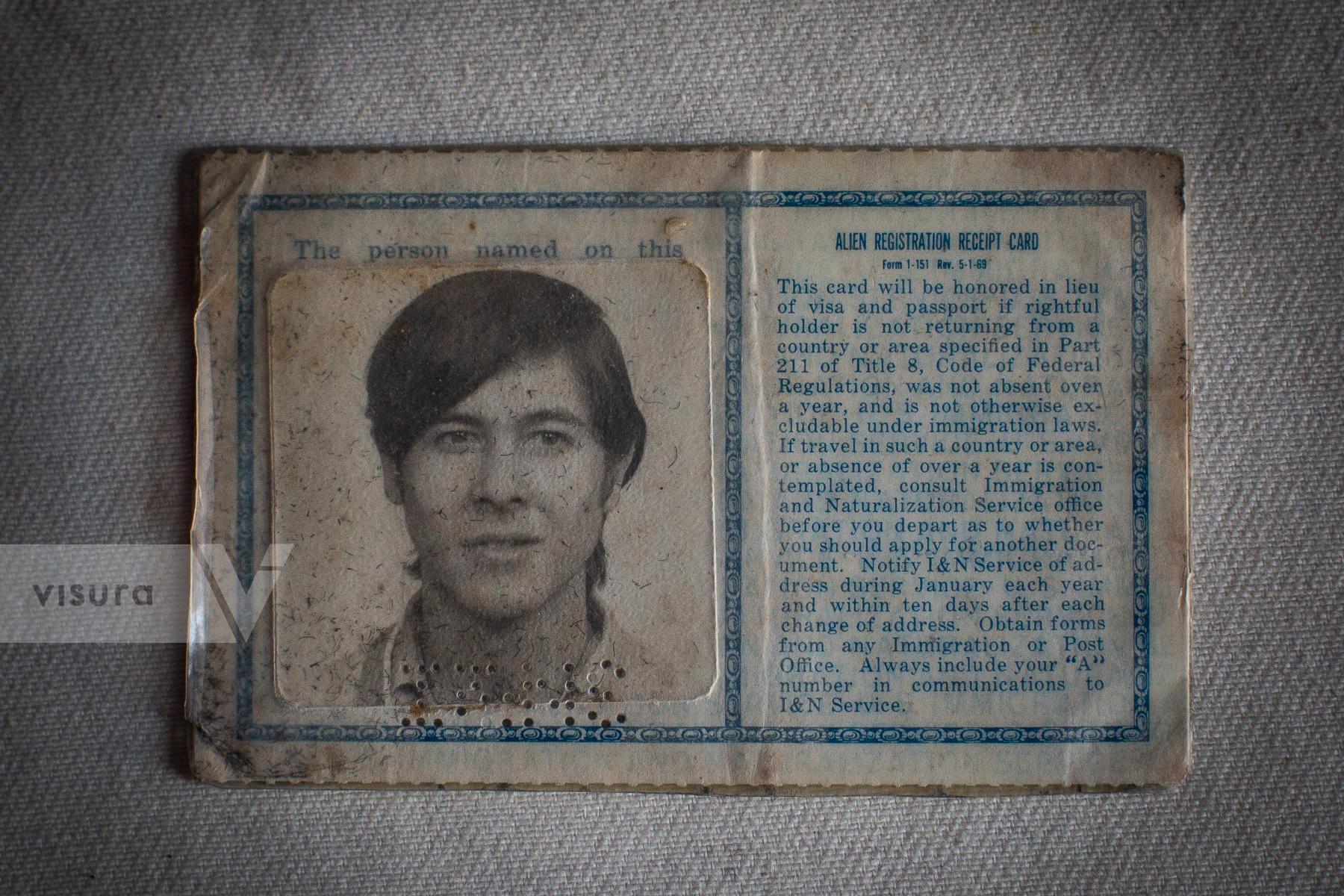

Jorge Machado’s Green Card, photographed in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 16th November 2021. When Jorge was about to be repatriated to the Azores, agents of the Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE) cut it in two his driving license because they defend that where he was going didn’t need it and that was only a privilege for Americans. According to Jorge, they didn’t cut his green card, because they didn’t find it. In Jorge’s mind, the green card made him an American, unfortunately, he never read the small print, he complained.

Under human rights law, the state power of deportation should be limited if it infringes upon an individual’s right to private life, and his or her ties to the country of immigration which includes: the length of legal residence in a country; military service in a country’s armed forces; legal residence in a country since childhood; and economic and business ties, according to a report by Human Rights Watch.

Evelina Bernardo shows a photograph of one of her sons, Ponta Delgada, Azores, on 28th May 2021. When deported, Evelina left the United States her mother, siblings, one daughter and three sons. The breaking of family ties due to deportation is one of the harshest burdens faced by repatriates.

The Human Rights Committee has explicitly stated that family unity imposes limits on states' power to deport. According to Human Right Watch report, the US deportation policies violate important human rights such as the right to family unity.

View of Santa Clara neighbourhood in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 7th July 2021. Santa Clara is a neighbour next to the harbour where many repatriated live and it is also the base of two NGOs that give support to them.

S. Miguel island is often called by repatriated “The Rock” or “Alcatraz” because they see it as a prison. “What I did, I did it there (in the United States), I shouldn’t have to come here to pay for it”, complained once repatriated.

Accompanied by a social worker, Evelina smokes a cigarette in front of Novo Dia’s shelter house for people with addictions in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 28th May 2021. Evelina is living in the same shelter house for more than 20 years, making her completely institutionalized. Without the help of “Novo Dia”, Evelina would probably not be alive anymore, especially taking into consideration all her health problems.

But even after so many years, Evelina is outraged with her situation. “I don’t want to be here, I hate this place. I’m doing a second sentence. It’s a life sentence”, she complains. According to Universal Rights, no one should be punished twice for the same crime, and their deportation after serving sentence is a clear violation of that right.

Fábio Medeiros gets hosed by a friend after exercising in the backyard of the shelter home where they lived in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 1st April 2021. Fabio was a child when emigrated to Canada and as a teenager started working random jobs to help his mother and his four siblings. He served 90 days sentence after two charges of domestic violence, and in 2020 was deported because he missed a probation hearing and couldn’t afford to pay a lawyer.

Unlikely most repatriated, Fábio saw his deportation as a way to start a new life with a clean slate. When he arrived he was given a place to stay in a shelter house and while he couldn’t find a job he passed his time exercising in the house’s backyard.

Amílcar Raposo watches videos of American sports on the computer at his home in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 21st November 2020. Like most repatriated, Amílcar doesn’t consider himself Portuguese.

The acquisition of a North American nationality was not considered relevant and essential for daily life. They entered the country at a very young age, and through a process of acculturation, most of their social-cultural references made them feel that they didn’t need to get a new nationality. In fact for many, in their minds, they were already fully Americans.

José Pacheco brooms the floor of the carpentry where he works in Lagoa, Azores, Portugal, on 10th December 2020. Pacheco is one of the few repatriates that found work through the NGO that shelters him.

Most repatriates can only get employment via a government program that promotes employment for a short period and with a very basic income. After finishing the program, most of them get into a permanent cycle of living on unemployment benefits and welfare assistance schemes, since employment opportunities for repatriates are very scarce.

Fábio Medeiros takes a break after being most of the afternoon breaking tiles on a construction site in Capelas, Azores, Portugal, on 17th September 2021. Even if he was used to all kinds of jobs in Canada, he confesses that working in construction is very hard and that feels like a prison, especially when he compares the income that he receives in the Azores with the one he got in Canada.

Younger repatriates like Fábio, tend to be more dynamic in leaving the precarious situation that they are facing, accepting the few opportunities that arise. They understand that this will be the only path to reduce their social exclusion and reach their idea of personal success which is to create a family, have children and reach material comfort.

José Pacheco (in the centre) picks up clothes with another resident of the shelter house in Lagoa, Azores, Portugal, on 18th December 2020.

Every resident that lives in the shelter home is responsible for daily tasks such as taking care of laundry, cooking and cleaning the house. These tasks create some routines and give a sense of responsibility to the residents of the house.

Residents of the shelter home celebrate José Pacheco’s 58th birthday, in Lagoa, Azores, Portugal, on 2nd June 2021. José was repatriated in 2007, leaving behind his parents, an American wife and a daughter. Since then he became a grandfather of two children.

The majority of repatriates don’t have any family on the island, and the ones that have usually are not welcomed due to the stigmatization that Azorean society reserves for them. Instead, they create social bonds and family ties with people that live with and face the same problems.

Fábio talks with his mother during one of their daily video calls from Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 30th March 2021. His father passed away when he was a toddler, and since he became a teenager he felt the responsibility to take care of her.

Fábio hopes that once he sorts his life in the Azores, he can financially help his mother and offer her a ticket so she can visit him. At the time of deportation, repatriates usually are told that with good behaviour they will be able to return after 10 years, but they never get permission to come back.

Jorge smokes a cigarette in his room in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 17th November 2021. Jorge retired after doing several jobs in the Azores and lives now with a small pension, in this little room where he spends most of his days watching television.

After fourteen years away as a free man, Jorge confesses that “I’m more lonely in the Azores than when he was in jail in America”.

Fábio Medeiros walks down the stairs with his belongings while moving from the shelter house into a new home in Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, on 6th November 2021. After months of living in a shelter house, Fábio managed to save some money and rented a room where he hopes to start his new life.

The recommencing of life for most repatriates is very difficult because of their age, the stigmatization from society, lack of working opportunities, several addictions and psychological issues that many faces. But to young men like Fábio that see a life full ahead, the opportunities might be different.

José Pacheco floats on the sea in the port of Lagoa, Azores, Portugal, on 11th September 2021. On the few opportunities that he has to leave the house during his free time, he likes to swim in the sea. Floating gives him a sense of liberty that he doesn’t have most of the time.

The feeling that many repatriated carried is of injustice since they are paying again for a crime that they already have served sentence for, which is a clear violation of a Universal Right that no one can be punished twice for the same crime. To them, a return to the Azores feels like they were sent to jail again. As one repatriated mentioned, “They give us our freedom, but here it doesn’t seem like freedom”.