Its nineteen years after the Rwanda Genocide and there remains with us a strong and lingering sadness. Like so many others, we believed the Genocide had ended once the killings had ceased.

In 1994 we travelled to Rwanda to document the impact of Australian troops in-country. In 2006 and 2008 we returned to Rwanda to look for traces of Australia’s involvement in the contemporary society. What we discovered was that for many survivors there is no life after the genocide. They have lost, and continue to loose, their health, their dignity, their security and their liberty. In many ways, through the omission of the Rwanda government and the international community to enforce notions of justice, the genocide continues. As Rwanda struggles to rebuild, survivors must live with perpetrators in an uneasy truce, with fear and justice denied. And once again the world looks on.

As we spoke to survivors it was obvious that many see their lives as finished and themselves as the living dead. Many carry the scars of the Genocide – both physically and emotionally. They shared their stories with us in the hope that people will care. We carry their stories so people will know.

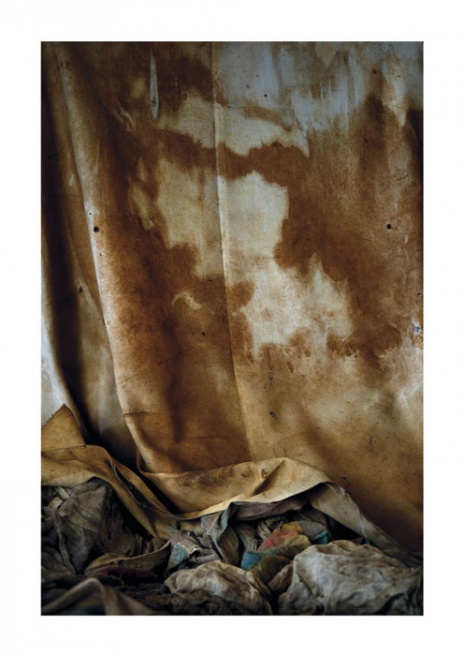

Over time we have come to understand that through their stories each validates their survival. These images (a synopsis) describe the grief and loss felt in Rwanda. We made each series in response to our encounters with individuals and our experiences of place. Text is incorporated, gathered from diaries and interviews. Its purpose is to give voice to the survivors. Images show traces of the their lives today; of how faith is maintained despite the enormous betrayal to so many. The Family Tree evidences the loss felt by one family across three generations: four survive from a family of thirty-seven. The massacre sites depict the ordinariness of spaces where genocidal acts took place. They are dotted extensively throughout Rwanda.

Angela Blakely & David Lloyd