My father died in June 2000.

My last memory of him is seeing him in a hospital bed. My first, of a man hunched over a desk, writing.

Sometime in the late nineties, my father and I decided to embark on a project about the unrecognized region of Karabagh: a remote Armenian region that we had hardly even heard of before its precipitous rise to the world stage as the first nationality conflict of the collapsing Soviet Union. A place that was part of our distant fatherland, where our forefathers had lived and died.

Until the nineties, neither one of us had stepped foot in that part of the Armenian homeland. Both our generations were born and came of age in the sprawling cities of the Armenian Diaspora: in Jerusalem, Paris, Beirut, Philadelphia, Los Angeles.

On New Year’s Eve 1998, I landed in Karabagh for the first time, alone. En route, our car hit ice on the dark road and came within inches of falling off a cliff. Mud at the side of the road saved us. In the dark, a car stopped, five men got out, pushed our car back onto the road. They told our driver to be careful.

I celebrated New Year’s Eve with a family I had just met. Their father: the lone survivor of his entire platoon. By miracle, he told me. They had two boys, one a baby. We ate and we drank. We drank to the memory of the men who fell in war. We drank to our fathers and forefathers. We drank to the future and to life. I returned home and within months I was a new father: my first son, Sebouh.

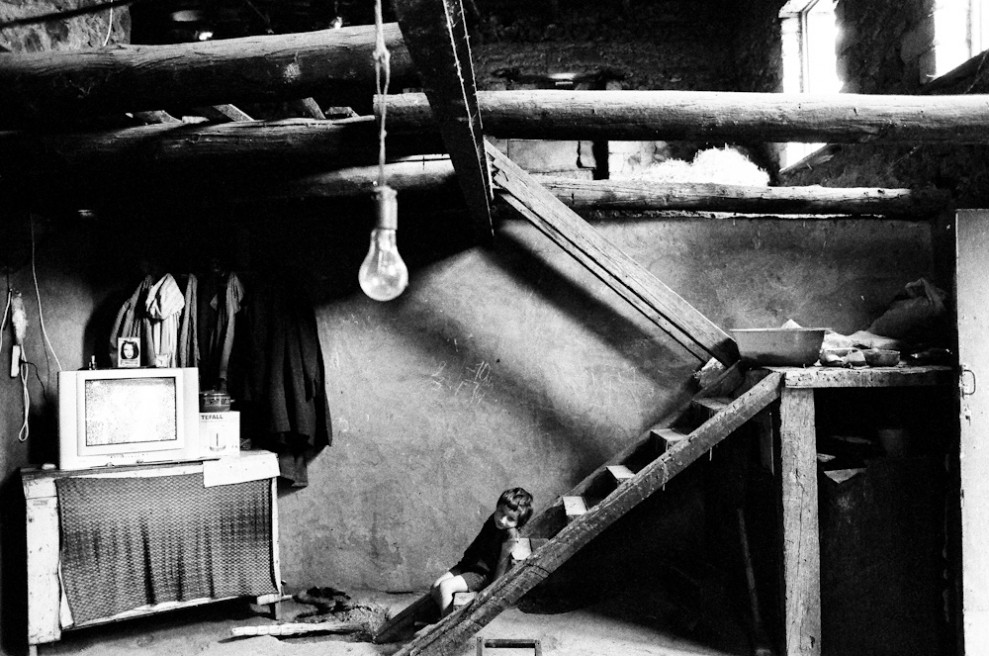

I returned to Karabagh in the fall of that same year, 1999, in the wake of that euphoria and madness of newborn life. This trip I made with my own father. The father and the new father, one writing, the other photographing: this land, this people, this way of life so unfamiliar to us yet so naturally ours. Working together and in parallel, working to bring something to life. Being witnesses. We ate and drank with the same family.

It would be the only trip I made to Armenia and Karabagh with my father. Next year, I lost him. His writing for our project was the last thing he completed.

In the spring of 2002, almost immediately after my second son, Adom’s birth, I returned to Karabagh. I wandered and I photographed. I saw soldiers at the front lines, I spent time in hospitals and homes for the aging, I witnessed a birth. I moved under the constant gaze of the generation of men who died in the war, whose images are omnipresent in public spaces, at school entrances, on the walls of every home. I ate and drank again with the same family. They had a newborn baby girl. They no longer had their grandmother. We drank to our fathers and forefathers. We drank to life.

During my last and final trip, in 2006, atop Karabagh’s mountainous heights, I got news that my wife was pregnant. Within a few months of my return my twin sons, Shahan and Aren, were born.

And so, unbeknownst to me, a process, a cycle seemed to conclude itself. A cycle of new life and death. A cycle that linked and begot generations. And a project seemingly intertwined in this cycle.

The loss of the father, the emergence of a father. The transfiguration of the son to see himself, finally after so many years, as the father. A transformation. A becoming.

Karabagh—the people, the land, the very way of life—in a similar transformation. Political, social, existential. A nation with a president, parliament, and military but not recognized as a country by any other country, victors in war but yet to win the peace, its process of self-determination and reconstruction still not concluded.

This FatherLand itself in a state of becoming, looking for its own father.