Public Story

Ashes and Autumn Flowers

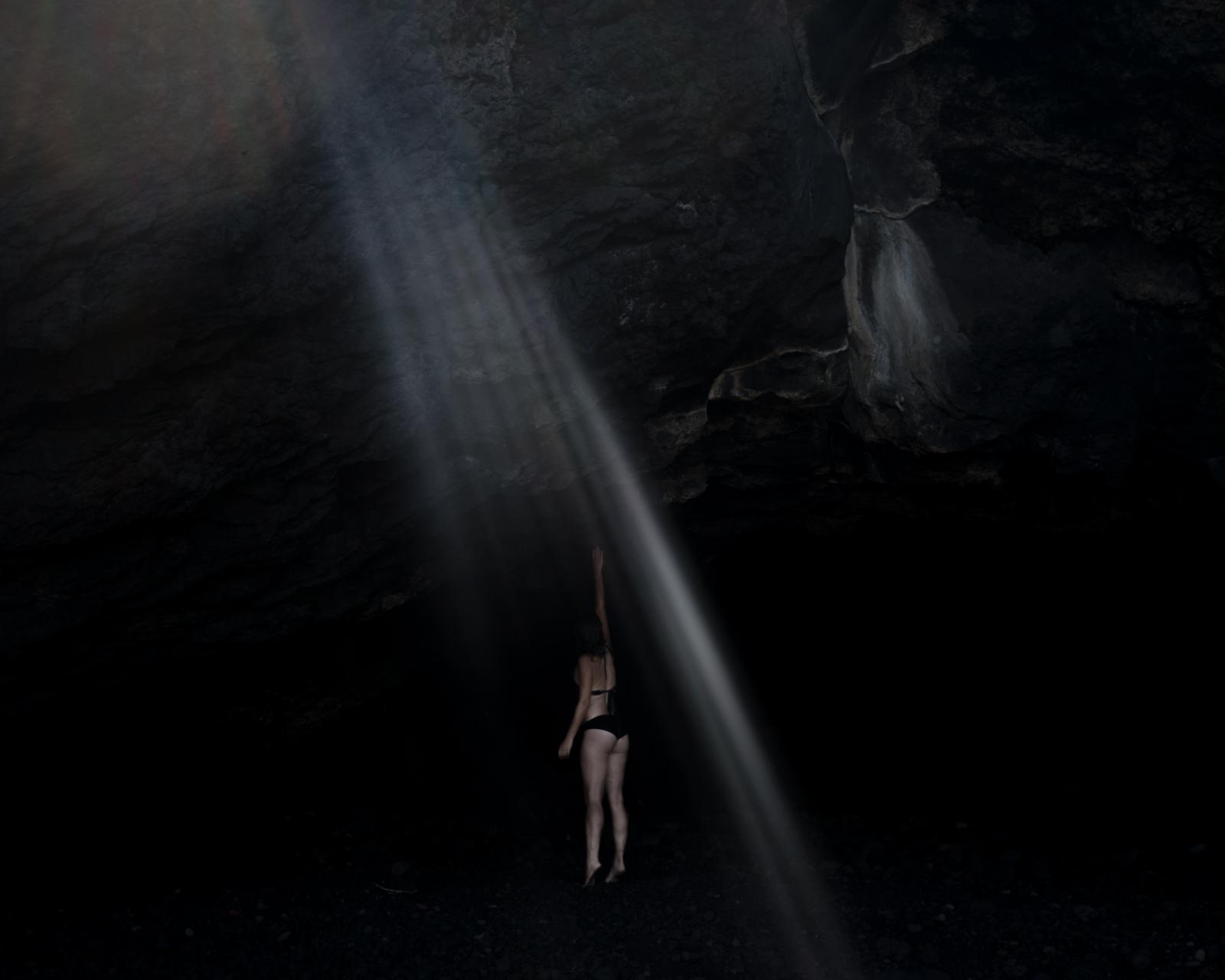

"Water is like fire: it’s a resource and a threat. A spectacle that contains a promise of tragedy, despite the daily happy ending.”

In Stromboli, Lidia Ravera

Stromboli is one of the most active volcanoes in the world, sprouting red fountains for the last 5.000 years. Ancient sailors used to call it “the Lighthouse of the Mediterranean”, as it helped them find orientation at sea during the night. Today people live in two villages, caught between the craters and the sea. Few were born there and fewer stayed. Others chose the rock as refuge from their own mistakes, from other people’s laws, from cars and high-rises. People come from various walks of life, but what equates them is living in a landscape whose often idyllic quiet hides a frightening power. Years spent on city streets can numb the capability to see mortality as a part of life and Stromboli helps regain perspective, scale down one’s own existence to negotiate a healthier relationship with it.

The island feels like a moonlit dream too charming not to be sinister. On its cliffs people stand on stones sometimes younger than them, shaped like the crest of sea waves by magma’s encounters with the wind, and the underlying tension, the “fire” that runs just under the surface, makes the fragility of human life somehow so tangible that it becomes acceptable.

I believe volcanoes stimulate something that human sensibility is not fully able to process, something that syncs in slowly. A feeling of peace blends with a shock that lingers in time, without a climax. They force us to stand in front of a past much more remote than the one we can mentally visualize, and a future we surely won’t be able to see. Thus, they bring us back to the only time we can really own.