Oil-shale plant own by VKG grup.

Kohtla-Järve, November 2021.

Map of Estonia and the Ida-Virumaa border region.

On the Estonian side of the Russo-Estonian border, people are sunbathing. In front of them stands the fortress of Ivangorod in Russian territory.

Narva, June 2022.

The Viru Keemiagrupp (VKG) plant in Kohtla-Järva processes oil shale. Using the stone, the plant supplies heat and electricity to the region, as well as several by-products such as oil, chemicals and bitumen.

Kohtla-Järve, November 2021.

Victoria, a young dancer is waiting for her moment to enter the stage. Today, Sillamäe is a town where cultural activities are scarce. The town was a closed and secret town during the Soviet era. Workers from all over the Soviet Union came to work on the construction of the Soviet atomic bomb. To motivate them, the city had facilities and goods that could not be found in other Soviet cities.

Sillamäe, May 2019.

In Kiviõli, a mining town, a slag heap has been transformed into a ski slope. Kiviõli (which literally means oil stone) was built around the oil shale processing industry. Today, the city suffers from the deindustrialization of the region. Through tourism the city diversifies its economic activity

Kiviõli, February 2022.

The town of Kiviõli (literally meaning oil stone) was built around the oil shale processing industry. Today, the town is suffering from the deindustrialization of the region.

Kiviõli, February 2022.

Raising of the Estonian flag to celebrate Estonian Independence Day, February 24. On the same day, Russia invaded Ukraine. It was a shock for all Estonians.

Valaste, February 2022.

Commemoration of May 9, Victory Day, on a Soviet T-34 tank in Narva, a city on the border with Russia. In the Ida-Virumaa region, where the majority of Estonians are Russian-speaking, the celebration of May 9 is of great importance and is a particularly sensitive issue. Many families have relatives who died in the Soviet army while fighting the German army.

Narva, May 2022.

In Marina Janssen’s hands is a photo of her grandfather holding Marina’s mother in his arms. Her grandfather died during the Second World War in the Soviet army. Every year on May 9, she used to march through the city with a portrait of her grandfather. This year the march was banned because of the Russian war in Ukraine.

Marina Janssen devotes her time to raising awareness of environmental issues among young people. She is very critical of the way the Estonian government is handling the transition to «greener energy production». She explains that she «had already been working since the 1990s on the search for a transition from dirty to clean energy. But nobody took it seriously. Now it seems to her that it is late and the ones who will pay the highest price will be the ordinary citizens.

Sillamäe, May 2022.

In August, the Estonian government decided to remove Soviet-era memorials. One of them was the T-34 tank memorial. For the Russian minority, this memorial was important. Here, volunteers placed flowers and candles at the site of the Soviet T-34 tank.

Narva, August 2022.

Tammiku is a small mining town. Despite the closure of the mine in 1999, cultural activities are organized in the cultural house. Here, a local band performs despite a sparse audience.

Tammiku, May 2022.

A conveyor belt transports oil shale stones from the Ojamaa mine to the VKG plant, which will produce oil, electricity and heat.

Ojamaa, November 2021.

At the Ahtme club during the «veterans’ party». The Ahtme club was a club for miners when the Ahtme mine was still open.

Ahtme was a town attached to the Ahtme mine. Today, many miners still live there. But most of them work in the Estonia mine or the Ojamaa mine, two of the last three mines in Estonia.

Ahtme, March 2022.

Anatoli and Igor Komisarov in front of the entrance to the Estonia underground mine. Anatoli and Igor are cousins and belong to the Komisarov dynasty. The miner’s job is passed on from generation to generation and is the pride of entire families.

Estonia mine, May 2022.

The Estonian oil shale stone is called Kukersite. It was named after the German name of the manor of Kukruse, in northeastern Estonia, by the Russian paleobotanist Mikhail Zalessky in 1917

Kohtla-Nõmme, November 2021.

Alvar (left) and Andres (right) are two brothers. Alvar works at the VKG oil shale processing plant and Andres works at the customs office in Narva, the border town with Russia. They enjoy a moment of rest in the sauna on a free weekend.

Ahtme, March 2022.

Anna and Katrin, two friends are enjoying a sunny winter day. They are sitting on a heating pipe.

Kohtla-Järve, March 2022.

A view of the VKG plant producing electricity and heat from oil shale stone.

Kohtla-Järve, March 2022.

Beach in Sillamäe. In the background, the Silmet factory processed uranium in the Soviet era, when the town was closed and secret. Workers from all over the Soviet Union came to work on developing the Soviet atomic bomb. To attract them, the city had facilities and goods that could not be found in any other Soviet city. Today, the plant no longer processes uranium but rare earths such as tantalum and niobium.

Sillamäe, June 2022.

Aleksei and his daughter Arina at home. Aleksei is a miner just like his grandfather was. He drives excavators in the underground mine Ojamaa of VKG.

Ahtme, March 2022.

Scientists from the Estonian Ministry of the Environment check the temperature of the Kukruse slag heap. This heap is one of the first in Estonia. It still burns in its heart. It is nicknamed the voclan of Estonia.

Kukruse, September 2022.

Juri Sala (56) is a former oil shale miner. He is now hired by the mine museum as a guide.

Kohtla-Nõmme, November 2021.

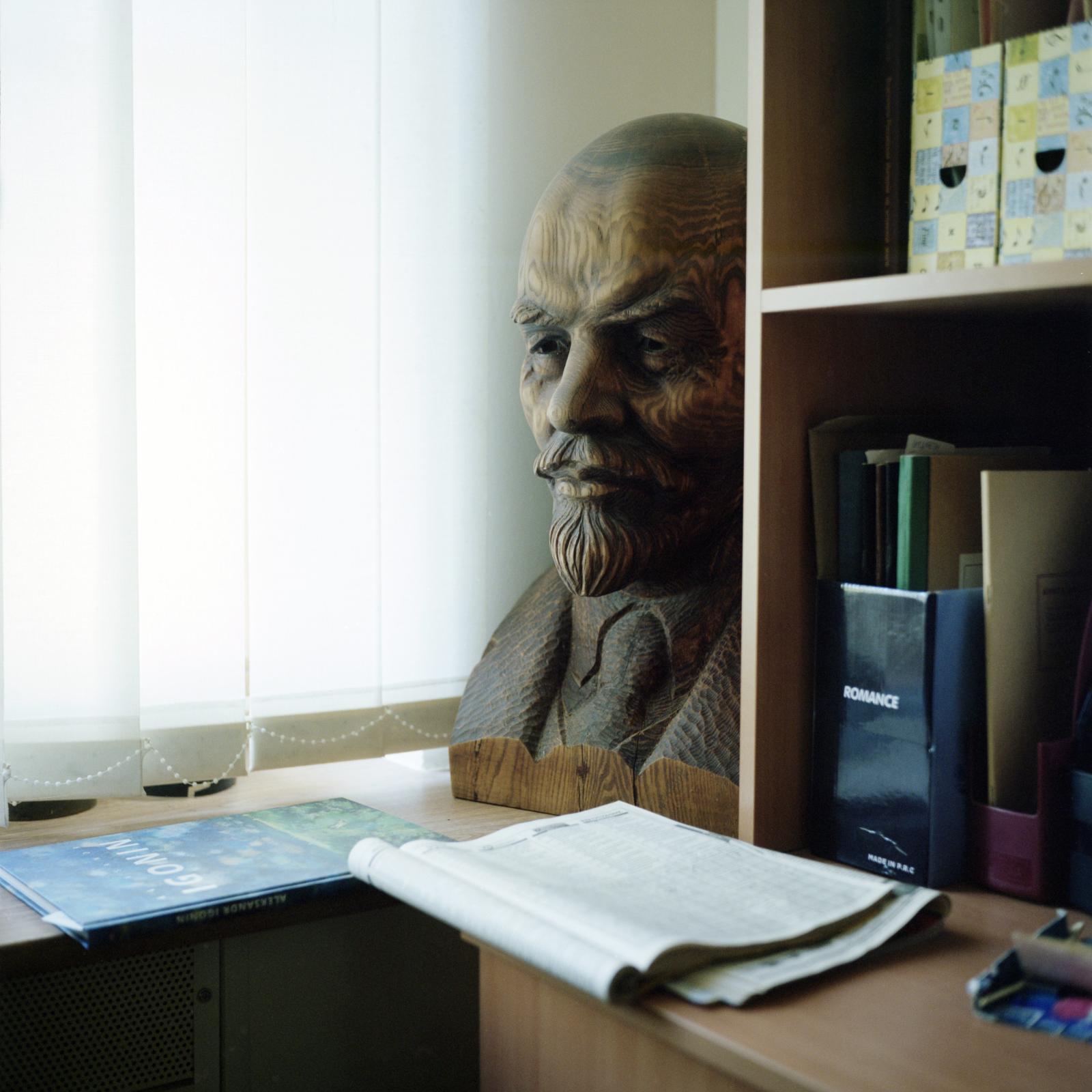

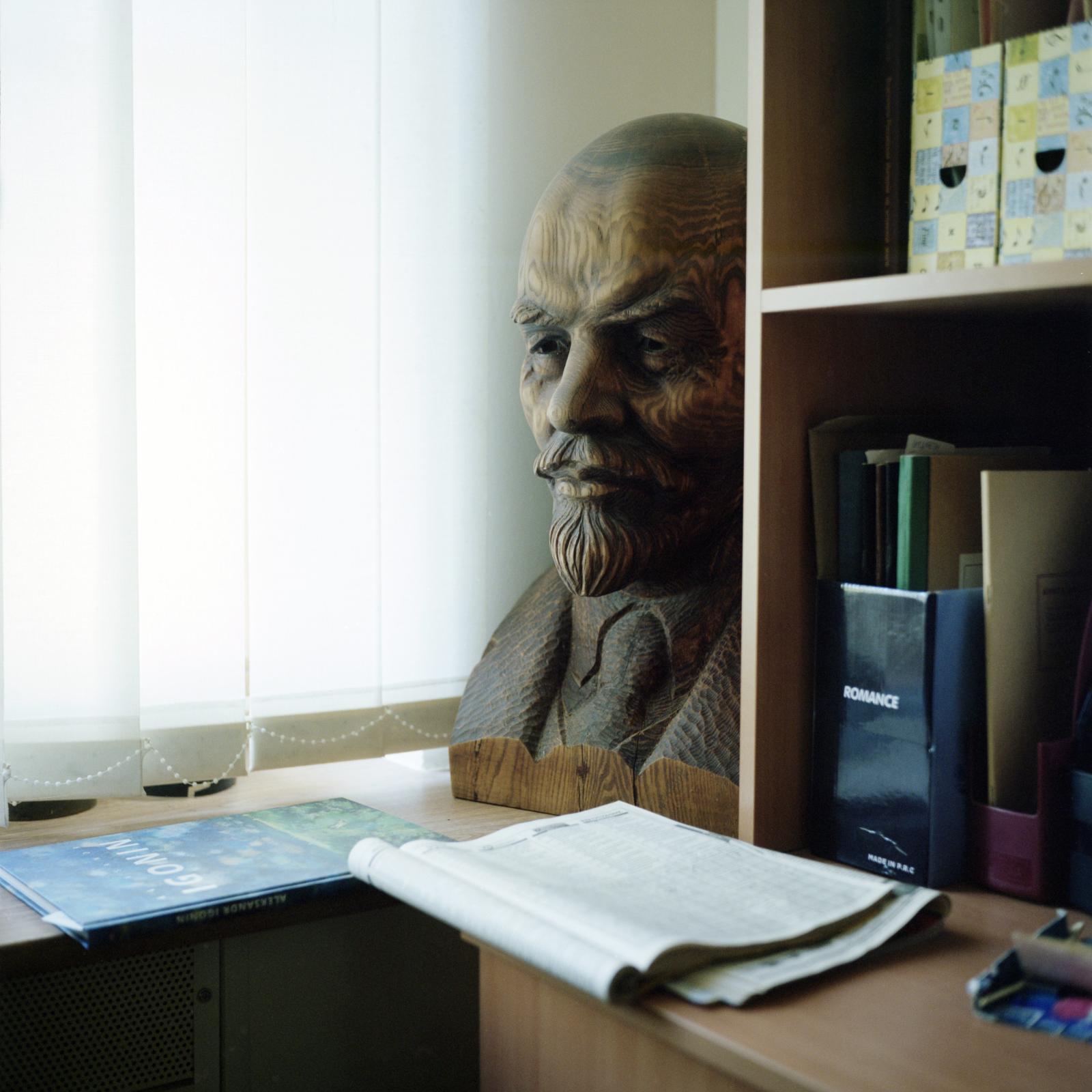

A bust of Lenin in the office of Aleksandr Popolitov, director of the Sillamäe Museum and a stone collector. Aleksandr Popolitov has dedicated a room to his stones in the museum; among them is the argillite stone, a sedimentary rock extracted from the oil shale around the town of Sillamäe. Argillite contains traces of uranium and was mined in Soviet times to develop atomic weapons.

Sillamäe, May 2019.

A statue of at the entrance of the Baalti Elektrijaam (power plant).

Narva, September 2022.

Estonian folk dances are important, especially among the Estonian minority of Ida-Virumaa. Although some Russian-speaking Estonians also sometimes join these groups. Here, the dance group Virvet is practicing at the Kohtla-Järve House of Culture.

Kohtla-Järve, November 2021.

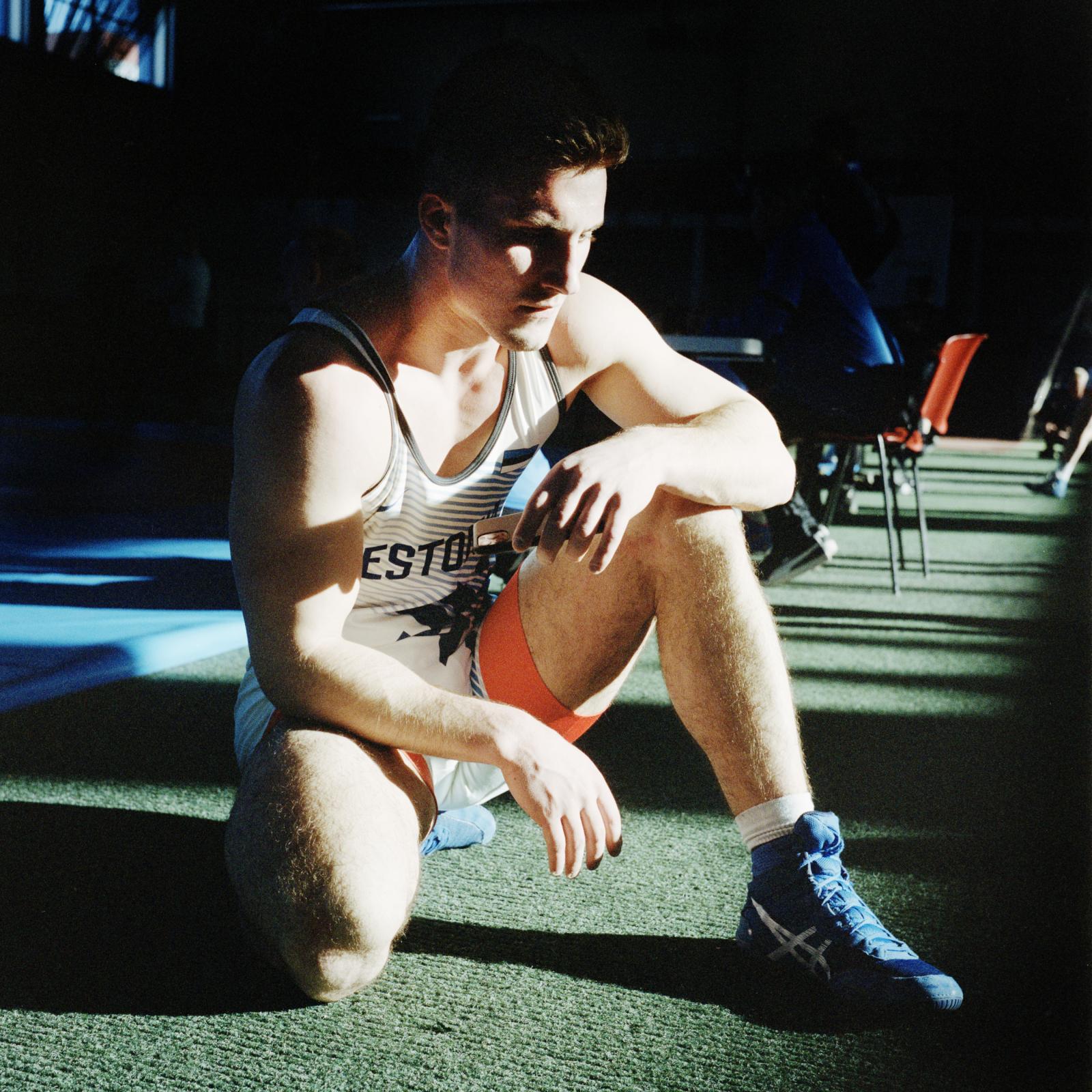

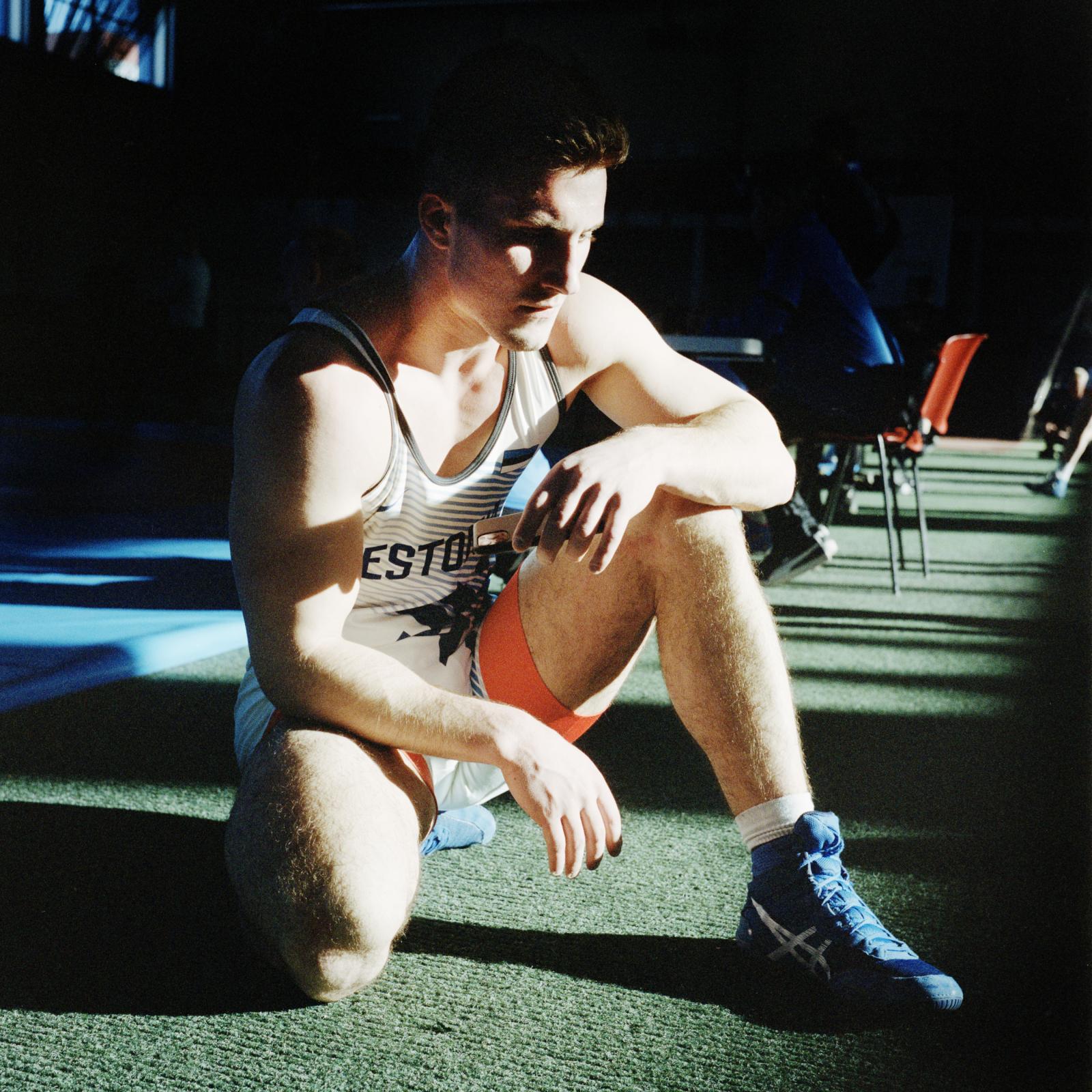

Jegor Tkatsjov, a wrestler at the 14th Estonian Winter Games after a fight. He finished 2nd in his weight category (86kg). Wrestling games were a popular sport among the miners, because it was necessary to show one’s strength. The miners used to train by carrying stones.

Ahtme, March 2022.

Scientists from the Estonian Ministry of the Environment measure the heavy metal content of water bodies covering former oil shale quarries.

Aidu-Nõmme, September 2022.

In order to move to a carbon-free system, wind farms are being built. But here, in a former oil shale quarry, the construction of a wind farm had to be stopped because it interfered with a nearby military radar.

Kohtla-Nõmme, November 2021.

A truck loads crushed stone from the Ojamaa mine in the old Aidu open pit. In the near future, a wind farm will be opened in the area.

Aidu, November 2021.

Artur, a teenager from Athme, plays in the town’s skate park. Ahtme is a town largely populated by miners. A mine of the same name was in operation until 1999. Today, most of the miners work in the Ojamaa mine or in the Estonia mine.

Ahtme, May 2022.

Ivan Korneyev is a former miner. He has received many awards during his career. He lives in the former mining town of Sompa in a house that was given to him by the mining company because he was recognized as the best worker. Today, Sompa is falling apart since the mine closed in 1999. Ivan refuses to leave the town despite the spartan living conditions.

Sompa, March 2022.

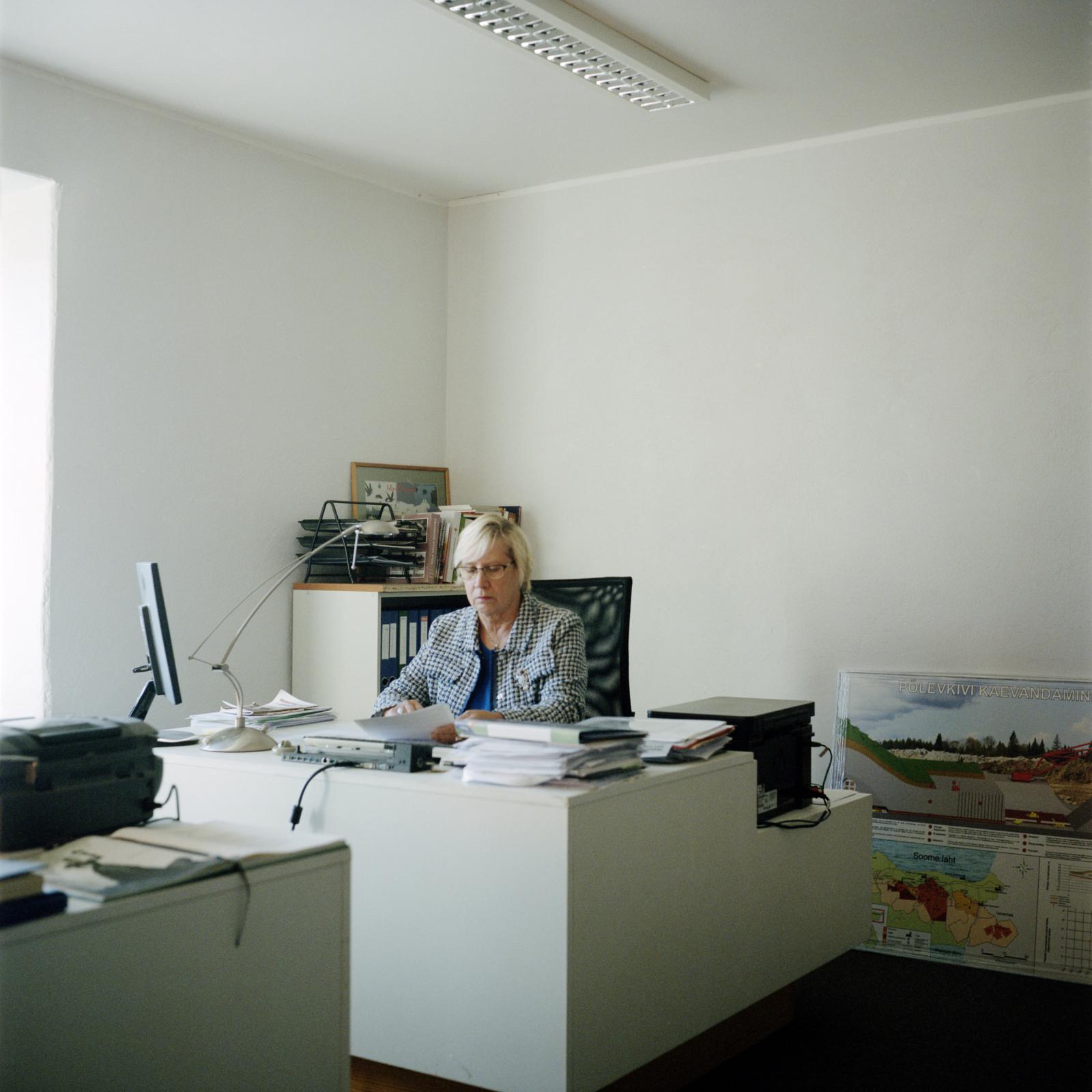

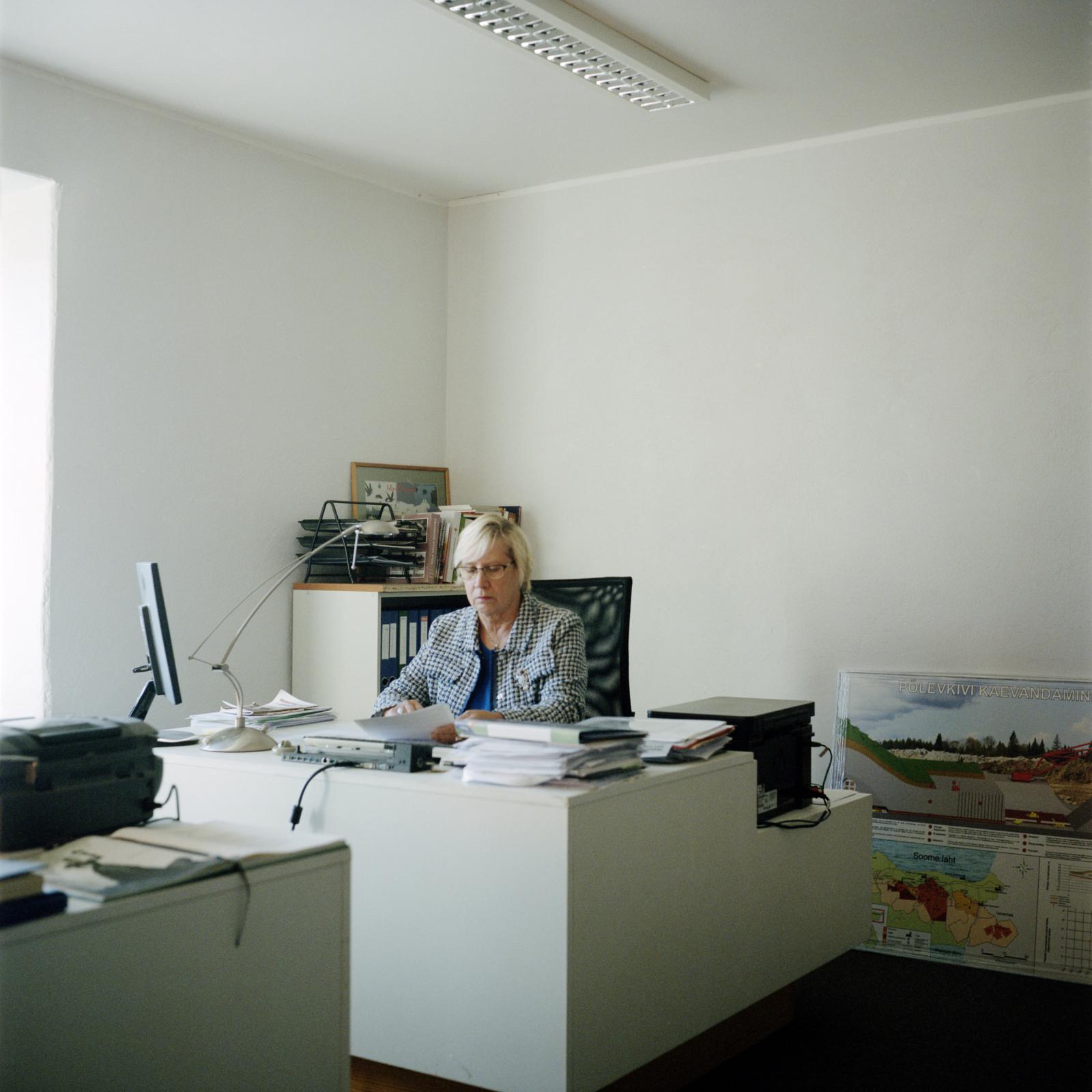

Etti Kagarov is the director of the Kohtla-Nõmme Mine Museum. When the Kohtla-Nõmme mine was shut down in 2002, it was transformed into a museum. Etti Kagarove is working to enhance the mining heritage of the region.

Kohtla-Nõmme, November 2021.

The open pit mine of Kiviõli is slowly nibbling away at the surrounding fields and forests. Here a piece of forest is nibbled little by little.

Kiviõli, September 2022.

A young couple, Artur and Vlada, are enjoying a warm evening on the banks of the Narva Reservoir, on the border with Russia.

Shared between Russia and Estonia, the waters of the reservoir feed, on the Russian side, the Narva hydroelectric power plant and cool, on the Estonian side, the two largest oil shale-fired thermal power plants in the world. Here, in front of Artur and Vlada, stands a slag heap.

Narva, June 2022.

View from a hill of crushed stone - mining residues - of the Estonia mine owned by the public company Eesti Energia. Eesti Energia plans to use the heaps as a recreational area for all-terrain vehicles.

Estonia mine, September 2022.

VKG power plant.

Kohtla-Järve, November 2021.