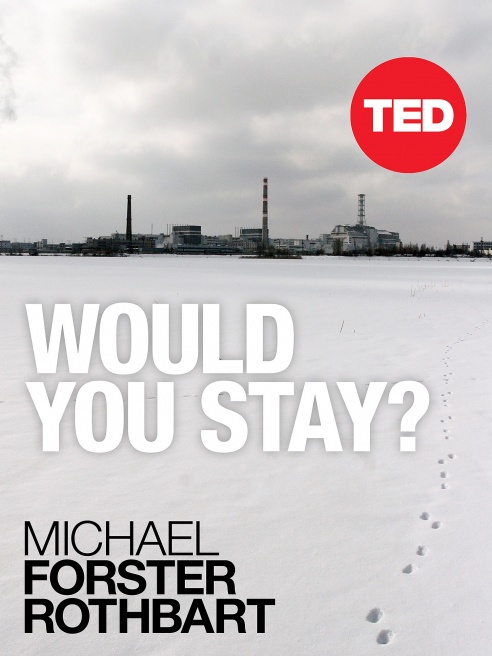

I am a photojournalist. In my work, I report on the human consequences of environmental contamination. This photo essay comes from my new book Would You Stay?, about the aftermath of Chernobyl and Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear disasters. The e-book, published in 2013 by TED Books (the same people who produce the TED Talks) uses photos, essays and interviews to explore questions about home: How do people cope when their homeland changes irreversibly? Why do so many stay?

* * * BOOK EXCERPT * * *

If you lived near Chernobyl or Fukushima, would you stay?

To the world, Chernobyl and Fukushima seem like perilous, forsaken wastelands. But for the people who live here " and yes, people do live here " danger is simply a fact of daily life.

The closer you are to Chernobyl, the less dangerous it seems. Instead of radiation, the residents of Chernobyl today focus on new fears. They worry about their future. Keeping their jobs. Opportunities for their children. Maintaining their hometowns.

In Fukushima, the experience of radiation is new " at least for anyone under 70 " and the impulse is to flee. For many, the search for safer ground has now shifted to worry that no ground is safe; the Japanese will have no choice but to learn, like the Ukrainians, to endure their fears.

I started photographing the Chernobyl region in 2007. My commitment to this project began when I discovered how most photojournalists distort Chernobyl. They visit briefly, expecting danger and despair, and come away with photos of deformed children and abandoned buildings. This sensationalist approach obscures the more complex stories about how displaced communities adapt and survive.

In contrast, I've sought to create full portraits of these communities. A Fulbright Fellowship enabled me to move to Sukachi village, 10 miles from the exclusion zone. I chose a dozen families and followed them over two years. I saw suffering, but also joy and beauty. Endurance and hope. Living directly in the villages where I photographed gave me access to events and people with an insider's perspective impossible from afar.

* * *

In Fukushima, it's been less than three years since the disaster. I started my new documentary project there in 2012. As in Chernobyl, I am trying hard to find a few typical people and stick with them long enough to witness their stories unfolding.

The pattern is similar for refugees anywhere, whether the cause is war, famine, or natural or environmental disaster. Syria, Chechnya, Rwanda. Somalia, Bhopal. Banda Aceh, Port-au-Prince, and New Orleans.The departure is so quick: Get out, while you still can. And the return is so slow. Painfully slow.

In most places, the danger passes. The war ends. The towns are rebuilt after the tornado, the hurricane, the tsunami. In Chernobyl and Fukushima, the radiation will not end. Not soon, not in our lifetimes.

How much radiation is safe? No one knows. With insufficient medical research, people believe rumors, propaganda, and their own firsthand experiences.

Why do people stay? A lack of alternatives. A sense of duty. Deep ties to the land. Decent jobs. Because this is home.

If you lived here, would you stay?